Davos 2026 AI Recap: From Pilots to Infrastructure

AI Governance, AGI Timelines, and What's Missing: Musk, Amodei, Nadella

Davos once styled itself as the place where climate commitments were made. A decade of pledges later, emissions are still rising, and the forum's signature cause has quietly slipped down the agenda. This year, AI took its place. AI crammed into the first four days that it deserves more than a passing mention. Elon Musk’s first appearance at the forum has only intensified the focus. What used to feel like a closed‑door talking shop now looks more like a place where real business gets done, and the voices people lean in to hear are the executives trying to execute, not the politicians reading speeches.

In AI Wrapped 2025 – From Hype to Habitat, I wrote that AI had stopped being a “topic” and become a condition, and that 2026 would feel “less like new tools and more like new constraints.” Davos just confirmed that prediction in real time.

Here’s TL;DR:

Across more than 20 AI‑focused sessions – and many of the 200‑plus panels that touched on it – AI is no longer treated as “emerging tech”. It is infrastructure and power.

Pilots are over; execution is mandatory. Most firms still get little or no value from AI, but those that redesign core workflows and build real AI operating models are starting to see serious ROI.

AGI timelines are shortening while transition plans stay thin. Leaders talk about powerful systems within 5–10 years, yet labour‑market disruption, reskilling and the much‑touted “120 million workers trained” pledge are wildly out of sync.

Less classic bubble, more concentration risk. Capital, talent and infrastructure continue to cluster in a tiny set of platforms, leaving thousands of thin “AI shell companies” sitting on top of other people’s models.

Compute, China’s AI+ model and a fragile risk map. Chips and energy are now tools of foreign policy, China is pushing an “AI+ everything” deployment strategy.

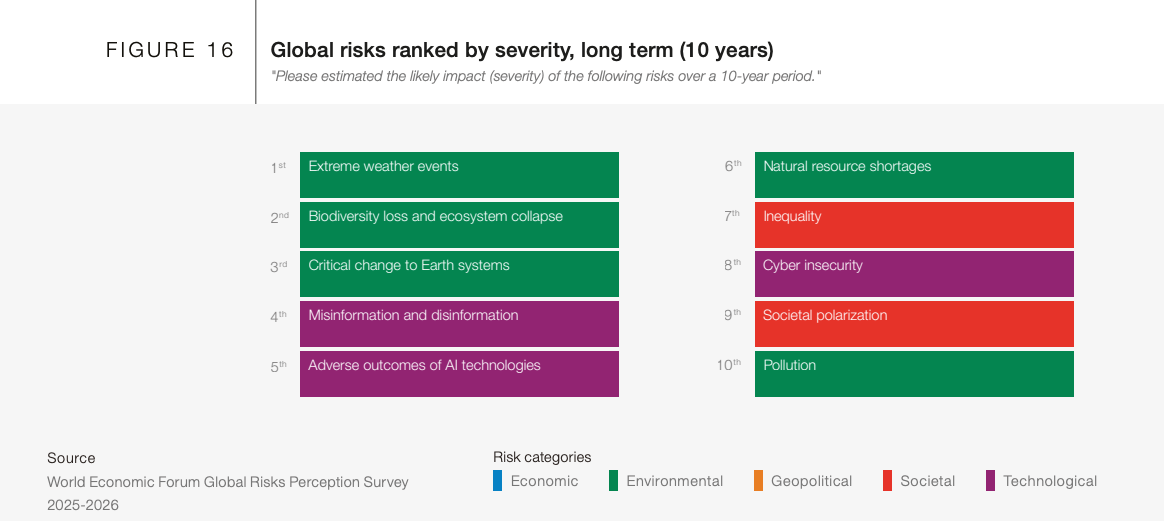

Global Risks

The 2026 Global Risks Report ranks “adverse outcomes of AI technologies” as the 5th‑most severe global risk over a 10‑year horizon, after extreme weather events, biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse, critical change to Earth systems, and misinformation and disinformation. That puts AI alongside classic environmental and information risks in the long‑term top tier, and many advanced economies now list AI‑related risks in their national top‑five risk profiles.

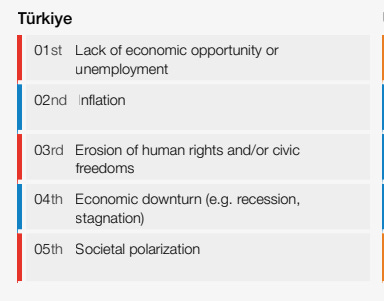

For Turkish friends; Türkiye, by contrast, has not yet “graduated” to worrying about AI at that level: its top national risks remain lack of economic opportunity or unemployment, inflation, erosion of human rights and/or civic freedoms, economic downturn, and societal polarisation.

Let’s get back to AI;

1. From Experimentation to Execution: The End of AI Pilots

In AI Wrapped 2025 the claim was that we had moved past the yes/no adoption stage: most organisations were “using AI”, but very few were compounding value because they treated it as a bolt‑on tool rather than something governed like a product lifecycle. Davos 2026 is where that gap stopped being polite and became the main topic.

“Artificial intelligence is no longer a project. It is becoming a core organisational capability.”

Speaker after speaker described the same trajectory: bottom‑up experimentation, proofs of concept, pilots that never scaled. That pattern was effectively declared dead. AI is now framed as core infrastructure, comparable to electricity or the internet; you do not isolate it in a lab, you redesign the building.

Honeywell executive Anant Maheshwari captured it neatly in a Davos interview, saying enterprises are “moving beyond experimentation to scale AI across critical functions”, and shifting from traditional automation to autonomy, where systems can “sense, think, learn, and act dynamically”.

Two numbers kept surfacing

PwC Global Chairman Mohamed Kande: 56% of companies are getting nothing out of AI adoption.

Celonis research: companies that build an AI Center of Excellence get 8x better returns than those running ad‑hoc initiatives.

The frustration is familiar. Adoption metrics look high; scaling metrics do not. Most pilots:

Start without clear business KPIs.

Stall when they hit real systems, messy data and unclear ownership.

Never become production infrastructure.

There are, however, a few real “post‑pilot” wins emerging.

Siemens CEO Busch pointed to digital twin deployments where output rose 20% while energy costs fell 20%, a rare example of AI and simulation delivering measurable ROI at scale rather than slideware.

Siemens chairman Jim Hagemann Snabe distilled the new mood in one line:

CEOs, he said, need to be “dictators” in deciding where AI gets deployed.

You can hear the fatigue behind that word. After a year of “everyone try ChatGPT and see what happens,” Davos is now calling for mandate‑driven change: pick a few critical workflows and force them through.

As one commentator put it this week:

“Those who fail to recognize this will keep running pilots. Those who do will quietly redesign their businesses while others are still debating the next experiment.”

Nesibe’s two cent

This is the turn AI Wrapped 2025 tried to name: from hype to habitat. Once you call AI “infrastructure”, the central question stops being “does the model work?” and becomes:

Who decides which processes are re‑designed around AI?

Whose jobs are automated, re‑scoped, or eliminated?

Who shares in the upside, and who absorbs the risk?

Those are questions about power, not tooling, and most organisations still do not have explicit structures to answer them.

The “dictator CEO” framing may be a sign of governance immaturity:

Many “participatory” attempts failed not because participation is wrong, but because decision rights and escalation paths were never clarified.

And if 56% of companies get zero value, that may not mean “push harder”; it may mean they’re picking bad problems, automating what doesn’t need automating, or building AI where process redesign alone would fix the issue.

In other words: execution might be the problem, but strategy selection is not innocent.

2. AGI Timeline Consensus and the Workforce Crisis

The Davos session called “The Day After AGI”, with Dario Amodei from Anthropic and Demis Hassabis from Google DeepMind, ended up as the reference point for almost every other AI conversation that week. Neither of them treated AGI as a distant thought experiment.

Both put the probability of human‑level AGI by 2030 around 50%.

Amodei went further, suggesting “Nobel‑level” capabilities in some domains by 2026–2027.

Inside his own lab, the change is already visible.

Anthropic engineers increasingly “don’t write code” themselves – they orchestrate, specify and supervise models that do.

He predicts models will handle most end‑to‑end software engineering within 6–12 months.

Elon Musk, who made a surprise appearance in Davos, went further in public. In his own conversation with Fink he argued that AI could be smarter than any human “by the end of this year” or “no later than next year”, and could outsmart “all of humanity combined” within five years, especially when paired with humanoid robots that he casts as the route to “sustainable abundance”. He talked about Tesla’s Optimus robots leaving factories for consumer markets by the end of 2027, robots eventually outnumbering humans and even providing elder care, and AI data centres launched into orbit on Starship-class rockets, linked by laser instead of fibre.

That is almost exactly the pattern the “agents” chapter in AI Wrapped 2025 sketched out: agents landing first in messy operational work, and developers becoming curators of machine output.

The macro picture

Amodei’s macro forecast is deliberately provocative:

One scenario he sketches: 5–10% annual GDP growth alongside 10% unemployment – productivity exploding while large segments of the workforce are left behind.

He uses the phrase “zeroth‑world country”: a small, highly leveraged group (perhaps 10 million workers) experiencing 50% GDP growth, while the rest stagnate.

Hassabis is more optimistic:

“More meaningful jobs will be created,” he argues, but concedes that internships and entry‑level roles will be hit first, and soon.

He notes that coding is easier to automate because outputs are immediately verifiable, whereas scientific discovery has slower feedback loops.

There was pushback on the ground as well. Workday’s CEO used Davos to argue that the AI displacement narrative is “overblown,” describing AI as a tailwind for incumbents like Workday rather than an existential threat, and focusing on integration into existing workflows instead of wholesale replacement.

Nesibe’s two cent

The crucial point is not whether the timelines are right. It’s that labs are acting as if they are:

Safety budgets, product roadmaps, and compute allocation decisions are all being made on a 4–6 year horizon.

If you believe AGI is imminent, it becomes rational to accept more short‑term collateral damage (displacement, instability) to “get there first.”

On the workforce side, Davos echoes the “ladder problem” I flagged in AI Wrapped:

IMF’s Georgieva warns that 40% of global jobs could be affected – enhanced, changed, or eliminated.

“entry‑level coding roles shrinking”, with juniors becoming AI supervisors.

The missing piece: junior roles are where people acquire tacit knowledge and social capital. If AI erases those rungs, it’s not just income that’s at risk; knowledge transmission is, too.

Sceptics will point out:

AGI timelines have been overly optimistic for decades; current confidence may simply reflect recent LLM progress, which might plateau.

Historical automation waves – from mechanisation to office computing – ultimately created more jobs than they destroyed, although with painful transitions.

The striking thing in Davos was not just the 2030 timelines, but the way behaviour has already shifted to match them. Frontier labs are budgeting, hiring and building compute as if they have a four‑to‑six‑year window to land something close to AGI. Governments, by contrast, are still writing discussion papers.

That asymmetry turns time into a political resource. If you believe powerful systems are imminent, it starts to feel rational – even responsible – to accept more short‑term disruption in labour markets for the sake of “getting there first”. Politically, though, telling people “this might upend your career, but trust us, it will be worth it later” is a thin proposition in societies where trust is already fraying.

3. AI Bubble Warnings and Economic Concentration

In a Davos conversation with BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, Satya Nadella offered a simple diagnostic:

“If only tech firms benefit, it’s a bubble. AI has to diffuse across every industry.”

It’s a useful line because it acknowledges something uncomfortable: current AI value capture is heavily concentrated in a handful of companies.

Nadella also introduced a new macro metric:

“Tokens per dollar per watt.”

He’s essentially saying: future productivity growth is a function of compute efficiency and energy cost, not just headcount and capital.

Fink largely agreed with the non‑bubble thesis, saying: “I think there will be big failures, but I don’t think we are in a bubble,” on the condition that AI adoption spreads beyond the hyperscalers into the broader economy, especially if the West wants to stay competitive with China.

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang pushed that logic further. In a Davos fireside chat, he rejected the “AI bubble” framing outright, arguing that we are building “a new foundation for the world” and calling AI the “largest infrastructure buildout in human history.” which we will discuss in the next section.

Two immediate implications:

Regions with expensive energy (for example, much of Europe) carry a structural disadvantage in the AI race.

The “AI arms race” is quietly becoming a grid problem, exactly as AI Wrapped 2025 argued: “AI strategy becomes energy strategy.”

He also took aim at what you and I both see a lot of in the market:

He criticised “AI shell companies” , firms that only call external models without embedding their own tacit knowledge. They don’t build assets, they leak them.

Nesibe’s two cent

Nadella’s diffusion test is a good first filter, but:

AI can diffuse horizontally (across industries) while remaining vertically concentrated (a few infrastructure providers capturing most profits). This is the cloud model.

The “tokens per dollar per watt” frame also exposes a governance problem. Energy‑hungry AI doesn’t just clash with climate targets; it forces governments into awkward trade‑offs: do you prioritise data‑centre permits over housing, grid upgrades over schools, export controls over cheap chips? Those choices are arriving faster than most policymakers expected.

That creates a deep tension with climate and local democracy. Fast‑tracking data centres and transmission lines is good for “tokens per watt”; it is much harder to justify when it means taking land from communities or pushing grids beyond what they can safely carry. If AI is going to lean this heavily on public infrastructure, the decision about where and how to build it cannot be left to private negotiations with a handful of hyperscalers.

4. The Compute Race and Chip Geopolitics

A joint WEF–Bain paper, Rethinking AI Sovereignty, quietly framed the infrastructure discussion in Davos in more structural terms. It shows the US and China capturing about 65% of aggregate global investment in the AI value chain, reflecting a full‑stack approach that very few other economies can match at scale.

The paper’s core argument: for everyone else, AI sovereignty should be reframed as “strategic interdependence”, combining local investments with trusted partnerships and shared regional capacity, rather than chasing an impossible end‑to‑end stack.

Then Huang gave the infra agenda with a slogan:

“There’s not one country in the world where you won’t need to have AI as part of your infrastructure, because every country has its electricity, you have your roads, and you should have AI as part of your infrastructure.”

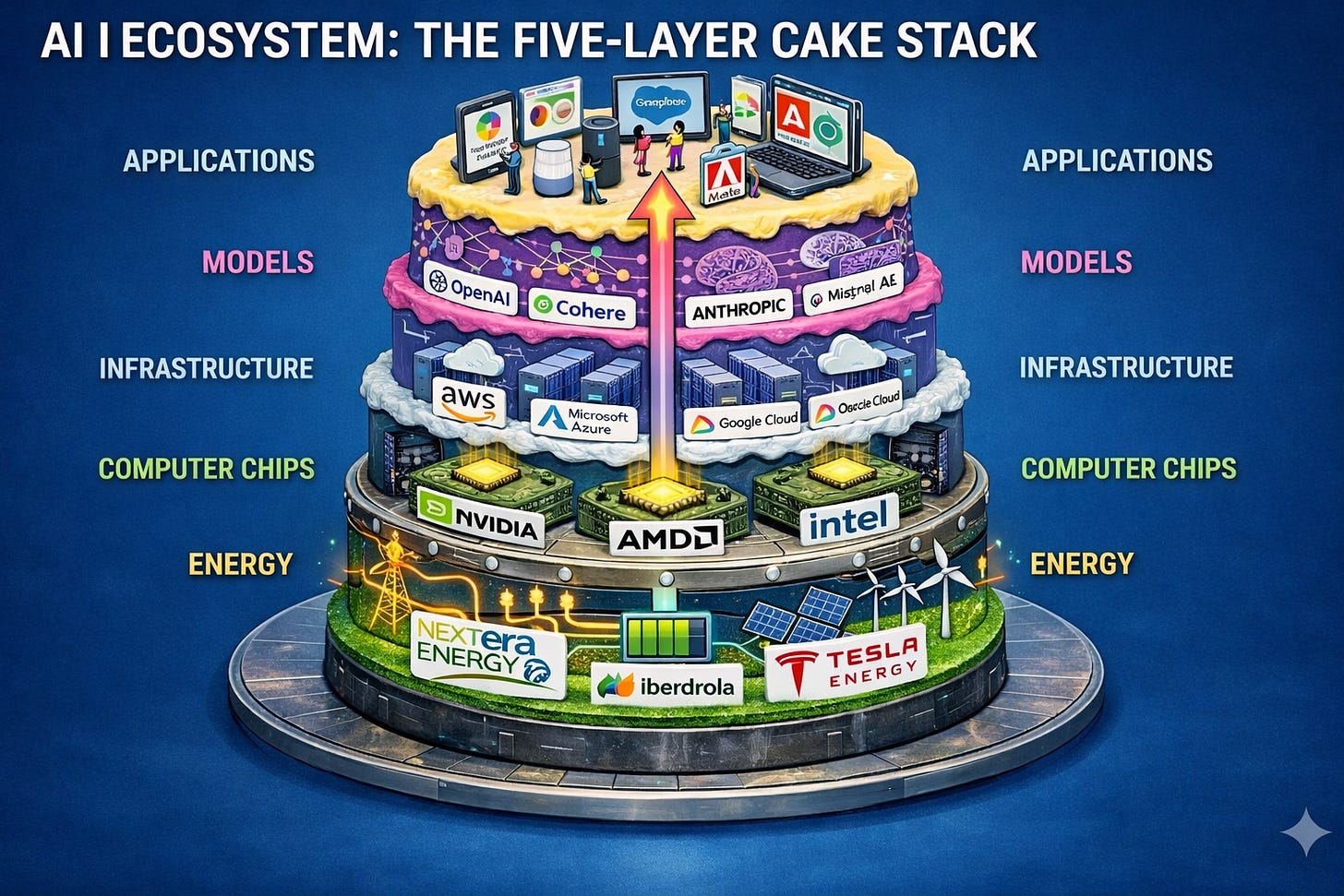

He laid out a five‑layer “cake”:

His argument: the spending looks huge because we’re building all five layers at once.

He cast AI build‑outs as a jobs engine – “plumbers, electricians, construction workers, steelworkers, network technicians” putting up data centres – and repeated that this is the largest‑ever infrastructure construction project, creating “a large number of jobs” that do not require a PhD.

For Europe, Huang suggested a strategic pivot:

Focus on AI robotics, where Europe’s manufacturing strength could offset its software disadvantages.

Chips as foreign policy

Dario Amodei delivered one of the starkest quotes of the week:

In his view:

Restricting advanced chip exports to China is the single biggest move the US can make to maintain its AI lead.

Slowing adversaries buys time to work on safety.

The broader technology landscape reinforces that logic.

Quantum computing is now routinely framed as up to around 2 trillion‑dollar economic opportunity by the mid‑2030s, with global public funding already in the tens of billions of dollars;

In the US, a bipartisan reauthorisation bill would extend the National Quantum Initiative through 2034, with annual authorisations of around $85 million for NIST, $25 million for NASA, and funding for new quantum centres, alongside a separate $625 million renewal for the Department of Energy’s quantum research hubs;

the European Union is preparing a dedicated Quantum Act;

China has folded quantum directly into its latest Five‑Year Plan as a strategic growth engine.

On a panel about China’s “AI+” Action Plan, officials and executives described a strategy that starts from infrastructure and diffusion, not from AGI heroics or ever‑larger single models. The ingredients looked roughly like this:

Heavy investment in cheap power and data centres, including the “Eastern Data, Western Computing” programme, which pushes AI and cloud facilities into western regions with abundant solar and wind.

Grid expansion on a scale that makes Western permitting cycles look glacial; a Brookings‑cited estimate puts China’s data‑centre electricity demand at about 277 TWh by 2030, a figure analysts note is large but not prohibitive given the country’s historic build‑out pace.

Policy targets that talk less about AGI and more about adoption rates – for example, intelligent terminals above 70% by 2027 and 90% by 2030 – alongside sector plans for manufacturing, finance, education and healthcare.

Stepping back, China’s AI+ path is not about “winning” a symbolic AGI finish line so much as about turning AI into basic infrastructure – like electricity or the internet – and using large‑scale adoption to remodel its production system. That is exactly what distinguishes it from the infra‑plus‑frontier‑model playbooks favoured in Washington, London or Brussels

Nesibe’s two cent

From a governance perspective, this is the point at which AI becomes openly securitised. Export controls, intelligence agencies and classified programmes move into the centre of the story. Critics of the chip‑control approach warn that strict export regimes may prove to be speed bumps rather than barricades, and could even accelerate efforts to build independent supply chains. They also worry that securitisation will weaken the very cross‑border cooperation needed for shared safety standards and incident reporting.

There is no plausible future in which AI is not a national‑security concern. The question is whether it is possible to build robust civilian and multilateral safety structures alongside that reality, instead of letting intelligence logic silently dominate.

5. Trust Crisis Meets AI Anxiety

While CEOs in Davos argued over AGI timelines and chip controls, another theme kept surfacing in side‑rooms, salons, and private dinners: trust is breaking down.

The 2026 Edelman Trust Barometer, unveiled at the World Economic Forum and based on around 34,000 respondents in 28 countries, paints a bleak picture:

70% of respondents show an “insular mindset” – they don’t want to live, work or even share a space with people who see the world differently.

Only 32% think the next generation will be better off (France: 6%, Germany: 8%, US: 21%).

65% worry that foreign actors are injecting falsehoods into their national media.

Over half of low‑income workers and 44% of middle‑income workers expect AI to leave them behind.

Richard Edelman describes a “five‑year descent”:

“Fear → polarisation → grievance → insularity. People retreat from dialogue and choose familiarity over change.”

Employers as the new trust anchor

One of the most striking findings:

“My employer” is now the most trusted institution, at about 78%, ahead of business generally and far ahead of government.

73% expect CEOs to act as trust‑brokers – listening to diverse voices and constructively engaging critics.

In other words: people are losing faith in public institutions and retreating into private hierarchies.

Nesibe’s two cent

The finding that employers are now the most trusted institution is both remarkable and troubling. It suggests that people are retreating from public institutions to private employment relationships as their primary source of stability and trust.

If employers become the primary trust brokers, they also become gatekeepers for information, arbiters of disputes, and de facto governance structures. As I explored in my November 2025 piece “AI and the New Class Lines,” this concentration of AI access through employment relationships risks creating new forms of stratification-where your employer determines not just your salary but your access to AI augmentation, creating a two-tier knowledge economy.

For AI governance, this means deployment decisions cannot be purely technical or economic-they’re inevitably political. How AI is introduced, who participates in decisions, what transparency is provided, and how benefits and harms are distributed will all affect whether AI adoption deepens trust erosion or helps rebuild it.

Some would argue that trust erosion is overstated or reflects unrealistic expectations. Historical trust levels may have been artificially high due to limited information access-people couldn’t easily discover institutional failures. Current distrust might reflect better information, not worse institutions.

Moreover, the focus on trust may distract from accountability. Strong institutions don’t require trust-they require mechanisms to detect and correct failures. The goal shouldn’t be restoring trust but building accountability structures that function whether or not people trust them.

6. What Davos Exposed by Omission

In AI Wrapped 2025, I wrote that governance had “stopped being theoretical” and become the main risk surface, especially as different jurisdictions pulled apart. Davos makes the gaps more visible:

Distribution mechanisms

Amodei’s “zeroth‑world country” scenario explicitly acknowledges concentration risk – 10 million people in an economic bubble, everyone else left behind.

No one on the main stages, in your material, offers serious mechanisms: public AI utilities, shorter work weeks, automatic dividend structures.

The conversation hovered between inspirational case studies and high‑level warnings, with very few concrete tools for finance ministries or labour departments.

Workforce transition infrastructure

Tech firms pledge to support 120 million workers by 2030 with training. It’s a big number until you set it against 40% of global jobs disrupted and AGI‑level forecasts.

What is missing is the dull but essential infrastructure:

income support for people who cannot bridge the transition in time;

portable benefits that survive through multiple job changes;

credible routes for mid‑career reskilling at scale rather than small pilot schemes.

In panel after panel, labour markets were still treated as slowly adjusting systems, even as the same speakers talked about AGI‑class systems inside a single decade.

Accountability for top‑down AI

We heard the call for CEOs to be “dictators” on AI. What we didn’t hear was how workers, users and communities get a structured voice in those decisions, or what recourse they have when deployment harms them.

Safety capacity vs. development spend

If, as Huang says, we are building “the largest infrastructure project in history,” AI safety budgets and regulatory capacity are still rounding errors by comparison.

Even inside the frontier labs, several high‑profile safety leaders have left over the past year, citing misaligned incentives. Safety work still looks, from the outside, like a support function racing to catch up with commercial ambition.

Alternative economic models

Almost all Davos discourse assumes AI will be built and governed by private firms and competing nation‑states.

Models like publicly funded open models, cooperative ownership structures, or tightly scoped public‑interest AI projects exist – but they are side conversations, not the centre.

Closing: Davos Asked the Right Questions. Now What?

Davos 2026 didn’t resolve anything – it rarely does. But it did something more important: it made the underlying contradictions audible. In AI Wrapped 2025, I argued that 2026 would be the year AI feels less like “new tools” and more like “new constraints” – energy, policy, and organisational reality catching up with the hype. Davos is the first big stage where those constraints are finally being named out loud.

The real test is what happens between now and Davos 2027:

Do we get binding governance frameworks with enforcement, or more voluntary pledges?

Do employers use their trust advantage to co‑design AI transitions with workers, or to push through opaque automation?

Do safety budgets and regulatory capacity scale with infrastructure, or stay as fig leaves?

AI will transform the economy either way. The open question – the one this TechLetter will keep coming back to is whether we build the institutional spine to make that transformation broadly beneficial, or leave the rules to the very few who already own most of the infrastructure.

I resonate with what you wrote, particularly your insightful prediction that AI would feel less like new tools and more like new constraints, which Davos seems to have perfectly confirmed. While the emphasis on AI as fundamental infrastructure is undeniable, I find myself contemplating the societal lag, where the swift pace of technological integration into 'new constraints' often outstrips our collective ability to develop adequate educational paradigms and public policy for the necessary human adaptation and reskiling mentioned.

Really thorough rundown of the Davos AI conversations. The point about 56% of companies getting zero value from AI while everyone claims adoption is one of those uncomfortable truths nobody wants to say out loud. Also think the "ladder problem" for junior roles is underrated as a risk, having seen how much tacit knowledg gets passed down through those entry positions in tech orgs.