Is AI Really Replacing Junior Workers?

The real question isn’t job loss — it’s ecosystem loss

Ever since we realized that AI actually works, one question has dominated everyone’s mind: “Will it replace me?” But this anxiety hasn’t spread evenly. It has hit white-collar workers the hardest — especially those in junior positions.

Yes, AI is having a far more visible impact on junior roles compared to other positions. In companies that adopted AI early, entry-level employment rates are declining 7–10% faster than the average.

But here’s the real issue: this drop can’t be explained by algorithms alone.

Because the system was already under strain.

Leaders today expect the people they hire and train to create not just short-term but sustainable impact. Yet the generation now filling entry- and mid-level roles sees work — and the concept of working itself — very differently from their leaders. Most of these roles are now being filled by Gen Z, a generation whose ideas of belonging, loyalty, and purpose diverge entirely from those of their managers.

Now, let me share a few datasets and analyses from different years and regions. I wasn’t surprised when I came across them, because they mirror what I observe every day:

According to FledgeWorks (2025), 65% of Gen Z employees change jobs within the first 12 months after starting. On average, a Gen Z worker is expected to change jobs ten times between the ages of 18 and 34.

The study “Generation Z and the Dynamics of Turnover: Insights from a Qualitative Study” (Safira & Ratnasari, 2025) shows that while the annual turnover rate among Gen Z employees was 32% in 2024, it rose to 44% in the first half of 2025.

The Deloitte Global Gen Z & Millennial Survey (2025) finds that 31% of Gen Z plan to change jobs within the next two years, compared with only 17% of millennials.

According to Gateway Commercial Finance (2025), 58% of Gen Z describe their current job as a “situationship” — meaning a role they hold without any intention of permanence.

A doctoral study at Walden University (Mikler, 2022) found that both millennials and Gen Z exhibit low organizational commitment and high intent to leave their jobs.

Put together, the picture becomes clear: the system now operates between two worlds — one where leaders expect productivity, loyalty, and long-term retention, and another where younger generations seek meaning, growth, and flexibility.

On the other hand:

According to the Hays Global Recruitment Market Report, by summer 2025, the job market will have “stopped getting worse,” but will remain stagnant. Uncertainty, cost pressures, and geopolitical risks are driving companies toward contract-based work over permanent hires. Net income levels have dropped by an average of 8% year over year. In short, this is not just a story of technology — it’s a reflection of macroeconomic caution.

At this point, AI steps in as a “solution.” Because viewing entry-level employees as a long-term investment has simply become too expensive.

Training a workforce that is difficult to satisfy, holds high expectations, and shows low retention is no longer efficient. Instead, companies are increasingly adopting a “delegate to AI” strategy. AI not only reduces costs but also redefines what “a valuable employee” looks like — in measurable terms.

Now that we’ve examined the background, let’s look at the extent to which AI is actually replacing entry-level jobs.

What Do the Graphs Say About AI’s Impact on Junior Roles?

The red graphs here are from The Economist, but the primary sources are listed beneath each chart. The most relevant data for us comes from “Generative AI as Seniority-Biased Technological Change: Evidence from U.S. Résumé and Job Posting Data.”

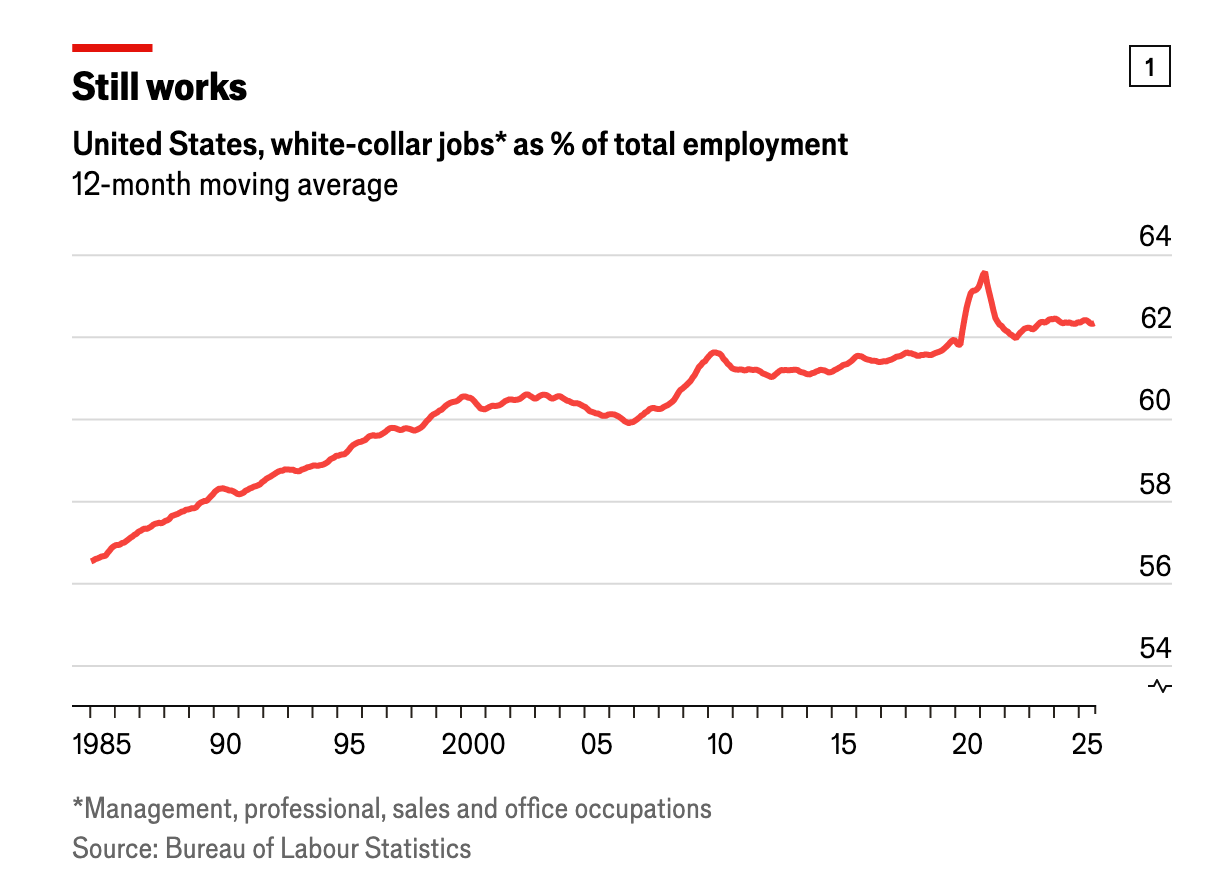

Bureau of Labor Statistics:

In the first graph, we see the share of white-collar workers in total employment. Since the 1980s, it has grown steadily — and even in the post-ChatGPT era, there’s been no dramatic decline. The system is still functioning; it’s just quietly transforming its shape.

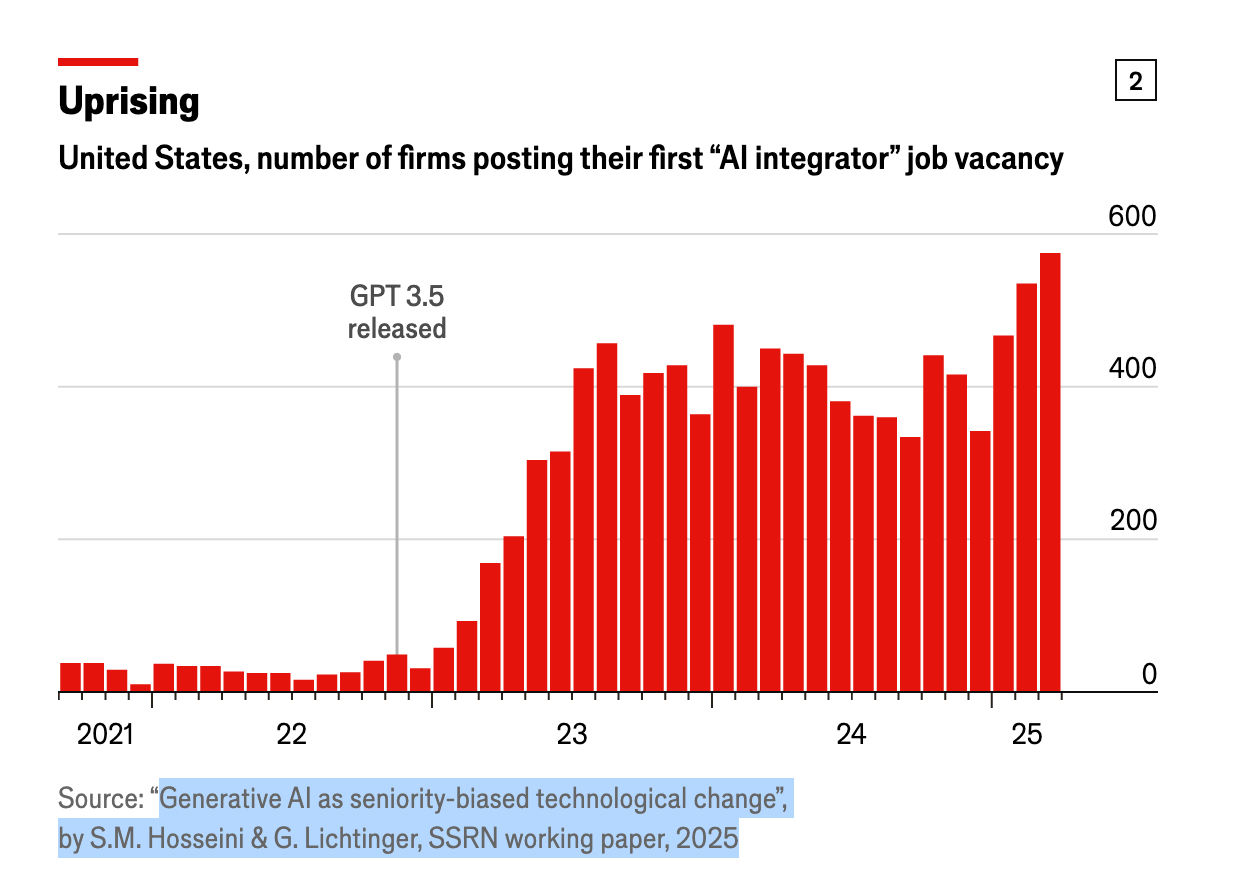

Generative AI as Seniority-Biased Technological Change:

The second graph shows the rise of “AI integrator” positions. After GPT-3.5 was released in 2023, these job postings increased sharply. Companies now treat AI not as a “project,” but as an integrated part of the business — a reflection of the shift seen across multiple labor market reports.

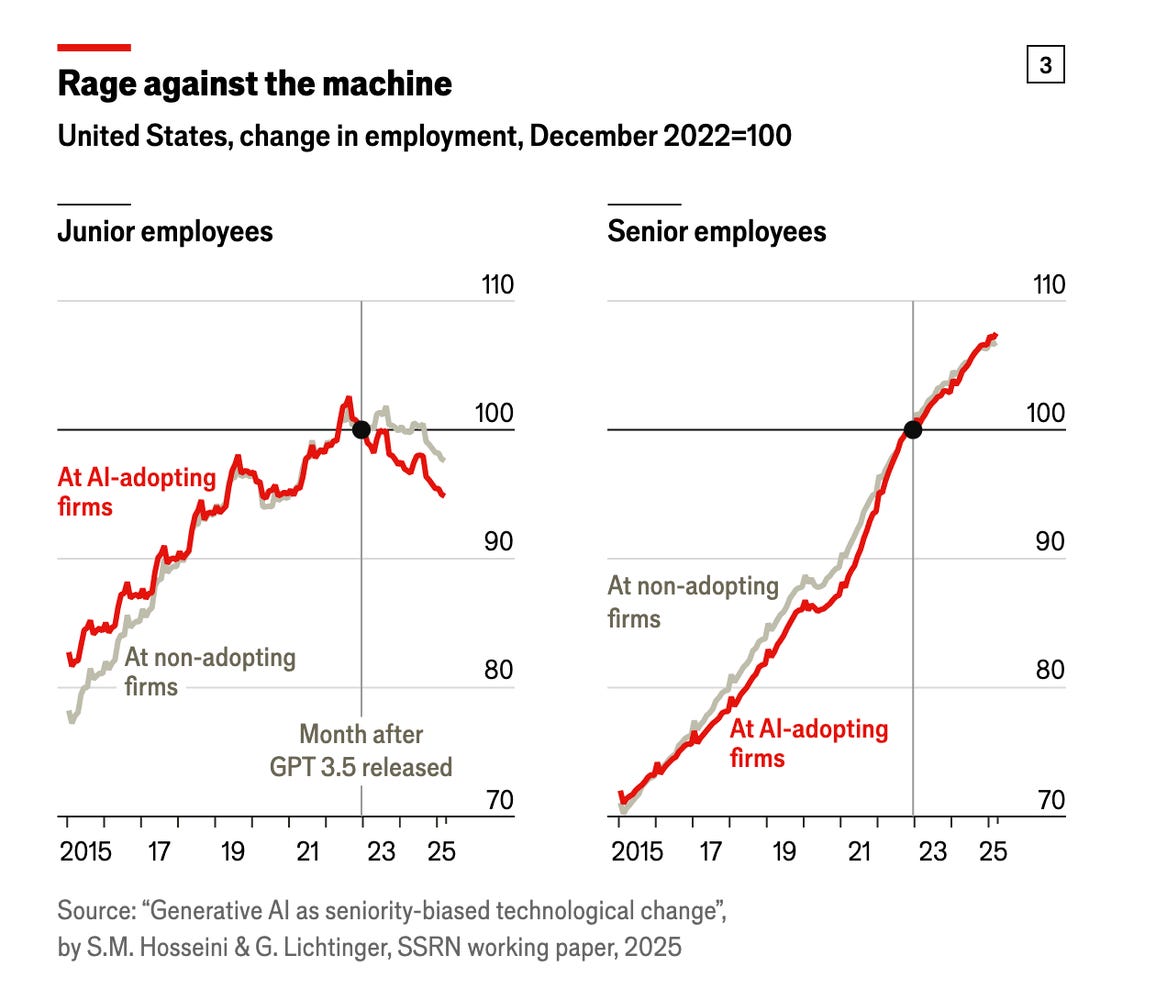

Generative AI as Seniority-Biased Technological Change (continued):

The third graph provides a realistic view of the decline in junior roles. The decrease is significantly sharper among firms that use AI, while senior roles remain unaffected. In other words, technology is redefining the lower rungs of the career ladder.

Stanford Digital Economy Lab:

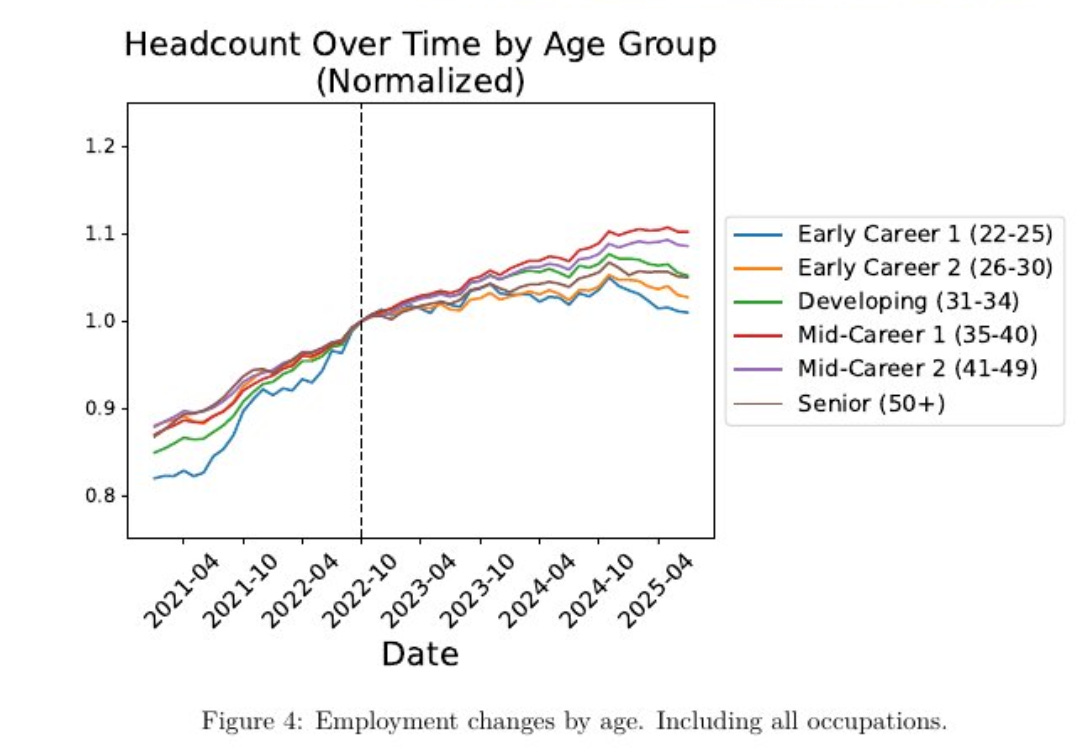

According to Stanford’s 2025 study, following the launch of ChatGPT (late 2022), employment among early-career workers aged 22–25 started to decline for the first time. Employment for the 26–30 group also slowed slightly. In contrast, employment among those aged 35 and above — especially 40–49 and 50+ — continues to grow.

From here, the question shifts from “Is technology taking our jobs?” to “What is happening to the gateway into work?”

AI isn’t primarily about eliminating jobs — it’s about narrowing the entry window. Entry-level roles are no longer seen as “learning grounds” but as “automatable processes.”

AI Has Begun Replacing Junior Jobs — Because the System Made Room for It

Today, AI has really entered the space once occupied by junior roles.

But this isn’t just the product of technology; it’s also the outcome of macroeconomics, generational culture gaps, and competitive speed.

Jobs that once served as learning environments for humans have become automation-friendly processes for companies — and temporary stations for young workers.

In this equation, AI hasn’t merely started taking over tasks — it has replaced the very meaning of entry.

As a result, the nature of early careers — learning through mistakes, growing through mentorship, adapting to a work culture — has become the easiest part of the system to sacrifice. If the lower layer of the system becomes hollow, the future experts will have nowhere to grow. And as this gap widens, companies’ internal talent pipelines will begin to dry up.

Fewer experts will rise from within — and how many decades can a company rely solely on “ready-made” experts from outside?

Such a structure cannot be sustainable, because every industry’s innovation once came from those curious “learners” who started as juniors.

But there’s another critical point here: we still don’t know whether the AI replacing young workers can produce sustainable productivity.

We’ll only see the real outcomes when the system faces its first test with a human-less lower layer.

That’s when we’ll realize the core issue isn’t job loss — it’s ecosystem loss.

Because without an ecosystem, there is no continuity of work.

AI may take over tasks in the short term, but it cannot take over learning, intuition, or human connection.

If we try to build meaning in the workplace through AI instead of strengthening organizational culture, the real fracture — the one that will matter — won’t be technological. It will be human.

That’s why:

Within the system we’ve cleared for AI, we must now build a new ecosystem where humans can still define their place.